|

Two Approaches:

|

Remember that the word "design" implies both planning and execution, which in turn implies that the designer

goes through a process. That process, whether lighting a play, dance piece, or opera, is highly subjective;

each designer has to develop a method which works for her or him. This, of course, can only happen

over a period of time and, depending on each individual situation, there may be slight differences in

process for each production.

Judy and Jeff have developed similar, but slightly different, processes. Here is Judy's:

This is a checklist and I've found through the years that if I go through each step, the

lighting will always be ok – more or less inspired, but always appropriate to the play, good

enough and trouble free.

- Before You Start: After you get

the job (even before pre-production meetings), acquire information on two

separate aspects:

- Technical: Under what conditions will

the play be produced?

- Physical: will it perform in

the same theater throughout its run?

- If so, what are the physical conditions of that venue? This

includes everything concerned with rigging the lights:

- What lighting positions are there? (Front of house,

over-stage electric or counterweight pipes, possibilities

for sidelights, footlights).

- Are there any problems or limits regarding the electrical

power supply?

- If the play will tour, what kind of theaters will it tour?

(size, limitations).

- Equipment:

- Does the theater have its own equipment or will it be rented?

- What options are there for extra equipment?

- Get a complete list of existing equipment, including:

- instruments

- dimmers

- control.

This should be a list of that equipment which is currently

functional and ready for use; it does you no good for a fixture

to be in the theatre, but broken.

- Routine:

Will the play be in repertory with other plays? If so,

- How frequently will the lighting be taken down

and reset?

- How much time will there be to light this

play before its first production? Before each subsequent

performance?

- People:

- With whom will you be working?

- How many electricians will be called for the first

production week, and for ensuing setups if it is in

rep/touring?

- Meet, if possible, the master electrician/ lighting director

of the theater.

- Artistic:

- Read the play: Read the play twice.

- First read it through just to gain your own personal

impression of it.

- The second time read it through with two different

sheets of paper.

- On the first, write down everything which

appears in the text itself which expressly

relates to lighting, because if an actor says

"it's getting dark" you'll usually

need to make it get dark.

In a different column write down everything

appearing in stage directions, because

these might not dictate lighting: they might

not be the playwright's instructions but rather

have originated in a previous production.

Even if they are from the original play, the

director and you could choose to ignore them.

In a third column write down any ideas or

specific lighting impressions that cross

your mind. Here's an example:

|

Page number

|

Text

|

Stage directions

|

Ideas/impressions

|

|

35

|

Anna: "it's dark in here"

|

|

|

|

36

|

|

Anna turns on light

|

Fluorescent?

|

|

38

|

|

|

Gets darker and spookier (evening falls)

|

- On your second sheet of paper, as you read, summarize the

play: Write down each act/scene number, and summarize in

a sentence or two what happens in that scene. This will

give you an idea of the dynamic development and structure

of the play.

- Research the play:

- Where is it set? If in a different country/time, what kind

of light would there be? Norway on a summer night is very

different from New York.

- If set in a previous age, what light sources would have been

used inside buildings? This way, when you do meet the

director and set designer, you will have practical

information to use in discussion.

- What kind of play is it?

- What style?

- Who is the author?

- What other plays has he written?

You may never need to use this knowledge, but it may help you

understand the director's concept, or it may help give you ideas.

- Who are the other people on your creative

team (director, other designers)?

If you don't know them, try

to find out what kind of work they have done before. For instance –

if this is a director who always does plays in his own

idiomatic style regardless of the play's own style or period, you should

know this before you meet him, and not start rattling off your new

found knowledge of the play's background.

- Preproduction:

- First meeting with the director, set

designer, other contributors. Despite all your research, in this

meeting you LISTEN. The director has thought a lot more about the play

than you have, and generally has some general conception of what she wants.

Your aim is to understand this and develop a dialogue. Oddly enough, the

best way to do this is not to talk much but to listen. If the director

starts out talking about what spotlights she wants, listen politely and

afterwards ask gentle questions aimed at understanding the general style

and conception. Doing this is an art in itself – one useful tactic

might be to ask indirect questions about casting, choice of music, etc.,

which will lead the director on to talk about concept. (It's often not

productive to ask bluntly "OK, what's your concept?")

- Subsequent preproduction meetings

will be held as the set and costume designs emerge, until the final set

model is presented. Here you want to be on the lookout for possibilities

and problems in positioning the lights, because this is where suggestions

can still be easy and effective (for example, building lighting positions

into the set when there are no openings for lights from outside.)

- Final pre-production meeting, where all

the technical people are present. This is your chance to request special

lighting equipment and discuss scheduling.

- Early Rehearsal Period:

At this point you don't have much to do since there is generally not much point

in watching rehearsals at this stage. It's a good idea to keep in contact with

the director and other designers, and you will be thinking about the play,

casting around for ideas, looking at paintings for example to try and clarify

visual ideas. There are two practical procedural steps I've found invaluable

at this stage:

- Visit the shop where the scenery is being built, as soon as there is

something to see. Often changes are made as the set is built and nobody

thought it would be relevant to you – but that open window you had

planned on lighting is now opaque fiberglass, for instance. Also often

you get clearer or new ideas when you see a set life size rather than

model size.

- Visit the shop where the costumes are being made – seeing the actual

cloth and costumes is important, often changes have been made from the

drawings, for instance the designer may have found a lovely brocade shot

with gold which was not in the original sketch.

- Runs-through

If you're lucky you'll get to see several runs-through but often

you are limited to one. During the run you do not sit back and let ideas

flow. You are busy all the time making two different sets of notes:

- Note down the mise en scene (who goes where). This may often

change later, but it's helpful to write it down for two reasons:

- It will aid you in talking to the director after rehearsal.

- It keeps you focused and prevents your mind from drifting

(just like taking notes in class.)

- Make a preliminary cue synopsis. This should include cue number, count

(time up/down), when the cue starts, what the aim of the cue is in terms

of atmosphere and effect, and specific lighting elements to be used. At

the start of rehearsal this will necessarily be limited to "lights

up slowly" etc., but as the rehearsal progresses it will become

clearer, and the counts will become more precise. You need both a

column for "what", indicating the feeling and atmosphere, as

well as a column with explicit lighting elements that you plan to use

for the cue; when executing the lighting later, you may find that your

choice of elements here doesn't work, and you will want to refer to

"what" for your original intention. You'll be refining and

reworking this cue synopsis later for use during plotting of the lights.

Example of a preliminary rehearsal version:

|

Cue

|

Count

|

When

|

What

|

Elements

|

|

1

|

3/9

|

Anna falls

|

Isolate Anna, not realistic

|

Spot down center (sharp and cold)

|

|

2

|

60

|

Jim: "Oh no!"

|

General daylight, happy feeling

|

Sun from window, warm backlight, warm wash

|

- Put together a list of lighting elements. This will be a simplified and

organized version of the last column of your cue synopsis. An element

is a light or set of lights which fulfill a single purpose. As a rule

this means they have the same or similar angle and color. Examples:

- warm diagonal backlight

- cool head-on acting area coverage

- greenish rectangular special down center

Afterwards you will translate the list of elements into a light plot,

but in fact the element list is your lighting plan; then it is just a

technical process to convert it into details of lighting instruments

with gels, channel assignments, positions.

After the run-through, you meet with the director, and this time you do

a lot of talking. You want the director to understand what you are going

to do, and you want to make sure it agrees with what she had in mind,

and what you have been talking about till now. If possible – if there is

time, and if the director is amenable to this kind of thing – it can help

to do "dry cues" – to go over cues in detail before the actual

lighting sessions.

- Plans

- Now you make a complete set of lighting plans:

layout and instrument schedule (see "Graphics"

and "Paperwork").

- At this point you should refine and update your cue synopsis. Add a

column with explicit channel levels and suggested intensities for each cue –

you may not use them, and the intensities will most probably change – but it

will help you get started and get over humps.

- Meet with the chief electrician to go over the lighting plot and

equipment list.

- Production

WARNING: Do NOT agree to go on to the next stage before finishing the current

one. For instance – don't start focusing till everything works, and NEVER start

cues before you have everything patched and focused!

- Setup: rig the lights, patch them, get

everything working.

- Focus: Aim the fixtures at the targets you want

them to light.

- Cues: Plot the lighting states. The

following people MUST be present during this step:

- Director

- Stage manager

- Board operator

- Stage walkers – people to stand on stage so that you are lighting

human faces and not just scenery.

People whose presence is helpful:

- Set designer

- Extra electricians to help make changes if necessary.

- Cue-to-cue rehearsal: With the actors,

go through the play just doing cues, and skipping the scenes. In a

particularly simple production it's possible to skip this and go straight

to a run through.

- Full technical rehearsal: If the

production is complicated, with sound cues, set cues etc., there should

be another rehearsal devoted to integrating all technical aspects of the

production.

- Runs-through of the play: There may be a

run through where you have the option to stop and make changes (personally,

I prefer to wait till after the run and then go back for corrections).

Afterwards there will be runs-through where you can't stop, but will have

sessions afterwards for corrections.

- Dress rehearsal and opening.

- Post-production

- It's your responsibility to leave a full set of plans including focus

plots, so that the crew will be able to recreate the production later.

- If the show is going to tour, you must also prepare a touring setup if

necessary, taking into account the different circumstances

(smaller theaters? Less time or crew for setup?) Since this obviously

involves more work than would a non-touring show, you should negotiate

the compensation for this at the time you accept the assignment.

- I generally try to go back to the theater for the second setup, if the

show is being performed in rotating repertory.

Jeff's process is much the same, with some slight differences:

- Read the Play.

I read the play at least three times.

- The first time is to get a general feel for the script and the playwright's

style.

- The second time, I am starting to get — and jot down — ideas.

- By the third reading, I'm starting to get serious about concept and

style. I can't think in terms of specific cues or looks, of course —

I have to know much more about what the director, actors, and other

designers are doing before I can do that — but I'm developing my ideas

as to how I want to approach the production.

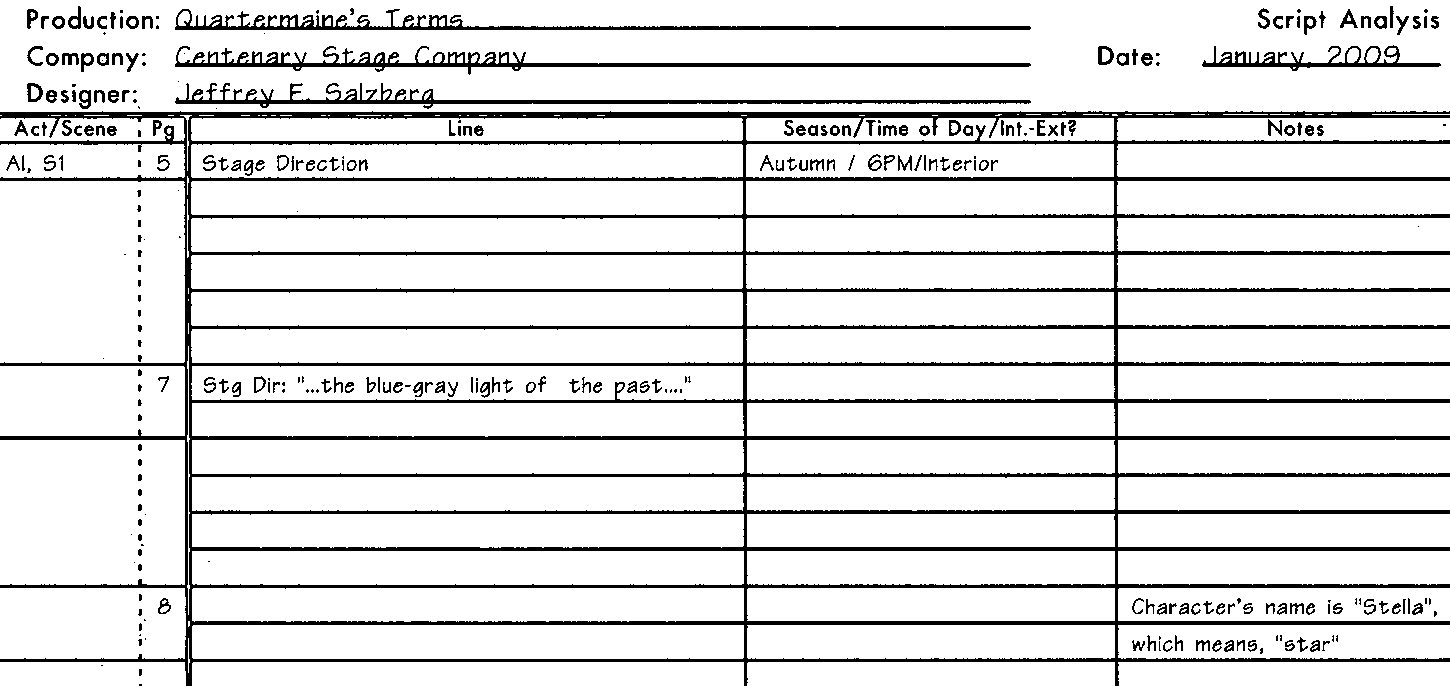

- Script Analysis.

During the second and third readings, I am beginning my script analysis, which

I do using a form such as this:

Notice the blank lines; I use this form throughout the rehearsal period and the

blank space allows me to insert items throughout the process.

Unlike the Instrument Schedule, Switchboard Hookup, and other database reports

(which are discussed in "Paperwork"),

whose primary function is to convey information to the electricians, the script

analysis form exists solely for the lighting designer's use in developing

her/his ideas. As such, the designer can have much more flexibility in terms of

layout and content; as you gain more experience, you can/should develop the form

(or forms) and system that work best for you.

Notice the blank lines; I use this form throughout the rehearsal period and the

blank space allows me to insert items throughout the process.

Unlike the Instrument Schedule, Switchboard Hookup, and other database reports

(which are discussed in "Paperwork"),

whose primary function is to convey information to the electricians, the script

analysis form exists solely for the lighting designer's use in developing

her/his ideas. As such, the designer can have much more flexibility in terms of

layout and content; as you gain more experience, you can/should develop the form

(or forms) and system that work best for you.

- Talk to the Director.

Now I'm ready to talk to the director. It's always preferable for him

or her to talk to me in concepts rather than in specifics — to tell me,

for example, that "this production is about man's inhumanity to man"

rather than "I want lots of blue light". Here and throughout the

process, it is much better if I can tactfully get the director to identify the

problem (for example, "it looks too warm") rather than dictate the

solution ("bring up the blues").

Even the busiest director probably does not direct more than eight shows a

year and on each of those productions, s/he has to think about actors and sets

and costumes and props....and lighting. I light between 15-20 shows a year and

all I have to think about is lighting. If I'm not more familiar with the

lighting vocabulary than is the director, the production has hired the wrong

designer.

For example, the solution to the above-mentioned problem ("it looks too

warm") may well be to take the warm lights to a lower level or to bring a

cool light elsewhere on stage to a lower level. (See the discussion of

"complementary colors" in the

"Color Mixing" section.)

If I have a blue and an amber near each other, they reinforce each other —

the amber makes the blue seem bluer and the blue makes the amber seem more amber.

Lowering the level of the blue will make the actors in the warmer light appear

to be less yellow...but this is a technique with which — while it might

be the superior approach in many situations — most directors are unlikely

to be familiar (and there's no reason they should be; that is, after all, why

they hired you).

- Watching Rehearsals.

I often find it helpful to watch early rehearsals, as this can give valuable

insight into the director's thinking. This is not always possible, especially

when the production is rehearsing and performing in a city many miles from my

home. Indeed, I have known some very good designers who substituted

substantial time watching rehearsals for time spent reading the script.

This has advantages and disadvantages:

- Advantages: The designer gets

insight into the director's approach, as well as that of the actors.

If the production has no script (dance concerts come to mind, as well as

some improvisational or developmental theatres), this may be the only

way to learn the show.

In the case of dance, I often substitute

watching videos for actual attendance at rehearsal.

This also has advantages and disadvantages:

- Advantages: I can watch the

piece many more times than I could watch a rehearsal with live

performers. I can also stop and start, and repeat sections as

I see the need.

- Disadvantages: Because video

is 2-dimensional, spatial relationships are often difficult to

determine. Union rules and/or copyright laws may preclude

rehearsals' being videotaped. In the case of new works,

choreography may not be completed early enough to enable me to

learn the piece in this manner.

- Disadvantages: Unless the

rehearsals are runs-through, I won't get an overview of the show

and I will lose the context of each scene. This method is also

extremely time-consuming. It is not always possible to see more

than one or two runs-through, especially if the show is being

presented in a city other than the one in which I live.

- The cues must be written (and preferably recorded into the console, assuming

it's a computer board) before the first technical rehearsal. You may well change

these over the course of technical rehearsals, but having them pre-written gives

you a starting point and keeps you from wasting the actors' time. Note that the

technical rehearsal is not where the lighting design is created; that happens

inside the designer's head. The tech rehearsal is where the design is first

realized and where the process of refining it begins. It is not the place for

actors to stand idly by while the designer laboriously builds cues one channel

at a time, nor is it the place for the designer to sit idly by while the director

and actors reblock the show.

It may take you some time to develop the ability to accurately write cues without

first seeing the lights on stage. Rest assured that you will eventually be

able to do it; like any other skill, it's an ability that develops with practice.

During the days of tech and dress rehearsals, cues will be adjusted or added

(or sometimes cut). Before and after rehearsals, and sometimes during actor

breaks, focus may be adjusted, and sometimes lights are added or moved.

I do not make these adjustments while the actors are "on the clock". This is

disrespectful of their time. Likewise, if I can make cue adjustments

"on the fly" (rather than while actors are standing around waiting for me),

I will do so, and I will do so in as subtle a manner as possible so as not to

distract the actors. When actors realize that you are courteous enough not to waste

their time, they are usually more patient at those times when you absolutely must make

adjustments in real time.

- By the time we reach the final dress rehearsal or preview (previews, as far as

this process goes, are in a neverland between dress rehearsals and performances.

I might make changes before or after a preview, but I am unlikely to make

adjustments during one), the show should be in its final state.

After final dress or preview, nothing other than the most minor of changes

should be made. We do not try things out on paying audiences.

|

|

The Rehearsal Arc:

|

Lighting designers come up against many different work situations,

ranging from extremely pressured, with only a few days to get a show

up, to extensive rehearsal periods as in some repertory theater

situations. We give examples here of two extreme situations:

Summer stock, where the schedule is very, very tight and the designer must have great technical skill

to get it done well, and a fairly leisurely repertory situation.

Bear in mind that these are only two examples; others include

lighting for commercial theater, for plays on tour, school plays,

community theater, and so on, and even within these two examples, there

will be an almost infinite number of variations.

First is a typical rehearsal schedule for an Equity summer stock production.

There are many different Equity contracts

(and, of course, you may be doing a non-Equity show), but this is typical for summer stock and even many

year-round small professional theaters:

13 days before

Opening Night:

|

First day of rehearsal. May start with a designers' presentation, at which the artists responsible for

the lighting, set, costume, and sound designs are asked to explain, in general terms, how they plan to

approach the production. As the lighting designer, you will not yet have seen any blocking, of course;

it is perfectly acceptable to say that you largely base your lighting on what the director and actors are doing

and therefore are not yet ready to discuss your concept. The first rehearsal may be preceded or followed

by a production meeting.

If the production is being rehearsed or performed in a city other than the one in which you reside, you

may not even have arrived by this point.

|

7 days before

Opening Night:

|

Production meeting.

|

4-5 days before

Opening Night:

|

Light plot and paperwork given to Master Electrician.

|

4 days before

Opening Night:

|

Designer run-through. A run-through of the play specifically so that the designers and technicians may

see what the actors are doing. It may or may not be the very first time the actors have run through

the entire play. You should certainly (with the director's permission) attend any previous runs-through,

as well as any runs of specific acts. After the designer run-through, you may need to make changes to the

plot and/or paperwork. These should be communicated to the Master Electrician as soon as possible.

|

3 days before

Opening Night:

|

Paper tech. The stage manager, director, and designers meet (usually not in the theater)

around a table and talk through the show, cue by cue. This is not the place and time for initial

discussion of design ideas; those should have been discussed previously in design conferences between the

director and the various designers.

|

|

|

Previous production closes. The set and lights are struck. The new light plot is hung and circuited.

The new set is loaded in and put together.

|

2 days before

Opening Night:

|

[Morning/Afternoon] The plot is focused.

|

|

|

[Evening] Technical rehearsal, with actors.

|

1 day before

Opening Night:

|

10-out-of-12. Under AEA rules, on one day during the week prior to opening,

the actors may work a 12-hour day (with a 2 hour break in the middle, meaning they

work 10 hours out of a total of 12). For designers and technicians, this often means

a "14-out-of-14", with work notes being done before the rehearsal and during the 2-hour break.

and a production meeting afterwards. Some Equity contracts allow more than one 10-out-of-12.

A typical 10-out-of-12 might follow this flow:

- Work notes, before actors' call.

- Finish teching the show.

- Run-through, with all technical elements.

- Work notes, during actors' 2-hour break.

- Actors' half-hour costume call.

- Dress rehearsal.

- End of actors' day. Production meeting.

|

|

Opening Night:

|

[Afternoon]. Dress rehearsal (some costumes may be unavailable), followed by production meeting.

|

|

|

[Evening]. First performance.

|

1 day after

Opening Night:

|

First day of rehearsal (next production). Production meeting and designers' presentation, as before.

|

Judy offers this typical rehearsal period for a repertory company working

within its own theater building. The exact schedule depends on the

complexity of the play and lighting. This example assumes a

complicated production with set changes, many sound and lighting

cues. For simpler productions less time will be necessary during

production week:

|

2-3 months before Opening Night::

|

First reading of the play. The designers are invited as well,

and if a set model is ready, it will be shown to the actors.

[Jeff notes that this time frame is typical in Israel and parts

of Europe, but in the US, it would be extremely unusual for

an Equity production to have more than a month's worth of

rehearsal time, although amateur and educational productions

may have rehearsal periods that span several months. The

other end of this extreme would be the

former Soviet Union, in which plays were often rehearsed for several

years before opening. Judy points out that even today, in

Europe, Israel, and the US, there are experimental theater

groups that rehearse for months and months and sometimes over

a year.]

|

|

2-3 weeks before Opening Night::

|

Run-through of the play, generally in a rehearsal

room, since usually the stage is full of the set for a

different production. Hopefully there will be more than

one run-through, but it's possible that after the first

run-through you will have to complete the lighting plot and

paperwork and submit it to the chief electrician.

After this (see: "process" above), you will talk to the

director and possibly have a session doing dry cues, at a

table; this depends on the director as well as on the

complexity of the lighting,

|

|

6-10 days before Opening Night::

|

Production week, which could last 6 days or even 10 (rare, except

in the case of opera).

- Day 1: Set-up of scenery and lights. If the

scenery would prevent lighting pipes from being lowered

to working height, the location of all set pieces will

be marked on the floor, and then lights will be hung

first and the scenery afterwards. If not, it may be better

to hang the lights when the scenery is in place.

- Day 1 afternoon/evening or day 2:,

depending on complexity of lighting and set:

Focus the lights.

- Day 2: "Dry tech" session to plot lighting

cues, with director, designer, and stand-ins on stage.

Separate session to determine sound cues and balance.

Separate session to practice set changes.

- Day 2 or 3: Rehearse the play going from cue-to-cue.

That is, the actors will begin, proceed through the cue

and continue until the director, the stage manager, or

you tell them to stop, and then skip to just before the

next cue, and so on.

If the lighting is simple this stage may be skipped.

Alternately, this rehearsal may be combined with a

general technical cue-to-cue, where sound and set cues

are integrated as well.

- Day 3 or 4: Technical rehearsal integrating all

aspects of the show. This may still be a cue-to-cue,

going through lighting, sound and set cues and putting

them all together for the first time. If so, the next

step is a full run through, which may be stopped if

necessary to iron out trouble.

At this point there may also be a dress parade, where the

actors try on the finished costumes and come out on stage

under lights, and the director and costume designer discuss

problems and alterations.

- Day 4 or 5: Run-through which is no longer dedicated

to technical problems but to the actors. This may already

be with costume. There may be runs-through in the morning

and evening, or there may be one run through a day and one

rehearsal with the actors to go over specific scenes.

The best situations are leisurely enough to have a couple

of days of full rehearsals. The lighting designer

generally will not be able to stop these rehearsals to

correct lighting, but may correct on the fly, or ask for

some time with the actors after rehearsal for corrections.

This period allows you to polish off the rough edges of

your work, fix timing, clarify and improve the lighting.

- End of production week: Dress rehearsal

(often with invited audience).

|

|

Opening Night::

|

First performance.

|

In true "repertory" theaters, the same play will run for a set

period, alternating with other plays. They may alternate once a week,

once every three days, or once a month, depending on the theater

routine. After the first performance, while the lighting is still in

place, the designer must meet with the person in charge of lighting

operation, to go over focus charts and insure that the focusing is

clear, so that it may be accurately reproduced each time the production

is restored.

|

|

The Lighting Designer and the Stage Manager:

|

With the possible exception of the Master Electrician, a lighting designer's closest and most symbiotic

professional relationship is with the stage manager. No matter how gorgeous your cues are, if they're not

called correctly, your work will have been for naught.

You will be working with the stage manager throughout the production process. Here are some things

to remember (with experience, these will become second nature to you):

- Make sure you and the stage manager are working with the same version of the script, with

the same page numbers.

In the case of most productions, this will not be an issue, but in the case of new plays, which

are in a constant process of rewrite and revision, and classics such as Shakespeare, which are

available in a number of different formats from a number of sources, it can be a very big issue indeed.

With a new play, even if your version of the script is identical to that of the stage manager, the

pagination may be inconsistent if your copies were printed on different printers (many playwrights

not having mastered the ability to insert "hard" page feeds).

This will become very important when you get to the point at which you and the stage manager

are discussing cue placement.

- Communicate cue placement to the stage manager in a timely and considerate manner.

Some stage managers prefer to get a list of cues that they can put into their books at their

convenience. Others prefer to sit down with the designer and go through the script. Some like

to write the cues during a "paper tech". A paper tech is a production meeting, before the first technical rehearsal,

in which the stage manager, the designers, and the director discuss the various cues and the general flow of

the production, without actually running the cues. It is often followed by a "dry tech", in which the cues are

run without actors (although it is imperative that someone be walking the stage).

In very rare cases, the stage manager may prefer to write the cues during the first technical rehearsal with

the actors. This is wasteful of the actors' time, and you should tactfully suggest one of the other methods.

Barring this, try to accommodate the stage manager's wishes, if at all possible. Her/his job is a difficult one

and anything you can do to make it easier will be appreciated.

- Tell the stage manager what the cue does and what the count is.

For example: "It comes up in 30 seconds and highlights DL" or "It emphasizes Tom's entrance."

The stage manager will usually be more familiar than you with the flow of the production

and, given this information, will be able to find the right place to call the cue. Of course, if

you're using the cue to provide punctuation, then you should communicate

clearly and precisely where you want the cue to start.

- Tell the stage manager, as far in advance as possible, of any booms or other obstructions

you plan to place backstage.

Likewise, notify him or her as early as possible of any backstage electrics work (for example,

changing gels) that will be happening during the performance.

- Also tell the stage manager of any autofollows.

- During the rehearsal period, do not wait until the last minute to give the stage manager large

numbers of cue notes.

Between technical rehearsals, you are likely to have several notes on cues that are cut, added, or moved.

Do not give these to the stage manager at the last minute, right before the next rehearsal begins. S/he needs

time to process the new data, ask questions about anything that may be unclear, and get the corrections

into the prompt script. In particularly fast-paced environments such as summer stock, you may have no alternative,

but try to get notes to the stage manager as early as possible.

- There are times when the interests of the lighting designer and those of the stage manager may seem

to conflict.

A common example of this would be those times when the lighting designer and the electricians are trying to complete

a focus call before the start of rehearsal and the stage management staff needs the stage in order to set up for the

same rehearsal. Another example would be the designer's need for "dark time" when stage management needs light on

stage in order to do their work. Remember that it's in everyone's interest for – and everyone wants –

all elements of the production to flow smoothly; find ways to compromise and ensure that you get what you need in

order to do your job well and others get what they need in order to do theirs.

AEA Stage Manager June Abernathy shares these thoughts:

[Special thanks to AEA stage managers Allison Deutsch and Erin Joy Swank.]

|

|

Neil Gaiman's 8 Rules of Writing:

|

In September of 2012, the NY Times published, as part of an ongoing series,

a list of "rules of writing" composed by

Neil Gaiman. With only minor editing, they apply equally to lighting design as well as to any other art form.

- Write. In the case of a lighting designer, if you're not currently lighting a show,

at least be thinking about lighting. Observe lighting in nature. Analyze other designers' work.

When you're listening to music, think about the way you would light each song. Look at paintings and

photographs and movies, and analyze the way those artists used light.

- Put one word after another. Find the right word, put it down. When you're starting a new project, don't be

intimidated by that big, blank piece of paper (or that big, blank, monitor screen). Don't think, "I have to draft

this whole plot"; think, "I have to draw the next fixture".

- Finish what you’re writing. Whatever you have to do to finish it, finish it. Self-explanatory.

- Put it aside. Read it pretending you’ve never read it before. Show it to friends whose opinion you

respect and who like the kind of thing that this is. In the case of the lighting design, this will almost

always be the director, and often the artistic director.

- Remember: when people tell you something’s wrong or doesn’t work for them, they are almost always right.

When they tell you exactly what they think is wrong and how to fix it, they are almost always wrong.

- Fix it. Remember that, sooner or later, before it ever reaches perfection, you will have to let it go

and move on and start to write the next thing. Perfection is like chasing the horizon. Keep moving.

The show's open. Move on.

- Laugh at your own jokes.

- The main rule of writing is that if you do it with enough assurance and confidence, you’re allowed to do

whatever you like. (That may be a rule for life as well as for writing. But it’s definitely true for writing.)

So write your story as it needs to be written. Write it honestly, and tell it as best you can.

I’m not sure that there are any other rules. Not ones that matter. Remember that theatre is a collaborative art

form, so you're not entirely free to just do whatever you want, but if you believe that your design serves the show — and

if the director agrees — don't worry if what you've done violates what the conventional wisdom holds to

be the "rules" of lighting design...even those listed elsewhere on this site.

|

|